by Justin Query

***

The spooky season may have come to an end, but there are aspects of horror that continue to mutate under the thin skin of terror that has no expiration date.

To that end, director Barry Levinson’s film The Bay stakes claim on the ecology of horror, suggesting that the monsters that could destroy us all are awaiting us as much as any homicidal killer trying to get into our home.

***

Since its earliest entries into the genre of horror, the subgenre of found footage has maintained a contentious regard by both fans and critics. Once, the narratives of Hollywood horror films were altogether traditional in their approach, but found footage films have allowed horror to go into remarkably creative directions, utilizing stylistic devices of substandard lighting, hand-held imbalance, awkward framing, and a complete acceptance by the film’s players that they’re being recorded. Ruggero Deodato’s stomach-churning Cannibal Holocaust (1980) made use of these devices while building its own story structure. Meanwhile, The Blair Witch Project (1999) turned the entire film’s production into an event, making use of the marketing campaigns that ostensibly fooled audiences that they were watching a horrifying documentary with a real-life body count.

Where these films deviate from one another is in their adherence to the definition of found footage films. By its most popular definition, found footage films appear to replicate the same conventions as mockumentaries, documentary films, and reality-based television, and The Blair Witch remains one of the most commercially successful films of its kind. Cannibal Holocaust, on the other hand, momentarily makes use of conventions employed by the subgenre’s second definition, which appears to more resemble home movies. What these two films — and others like Afflicted (2013), V/H/S (2012), and more — have in common is that they’re both rooted in horror, which remains a more psychological or unconscious activation of the audience’s fears.

But other found footage films marry these stylistic tropes in a much more conscientious manner, blending elements of both definitions in order to develop a hybrid of found footage styles. These films can also be less concerned with invoking the audience’s visceral fear in the subject matter and more concerned with raising consciousness, as is done in the genre of science fiction. One such film of this kind is Barry Levinson’s genre-defying film The Bay — which turns 10 years old next year — and remains a significant evolution in the library of found footage films, utilizing its stylistic methods to profoundly comment on the fragile nature of the world’s ecology and mankind’s complicity in its destruction.

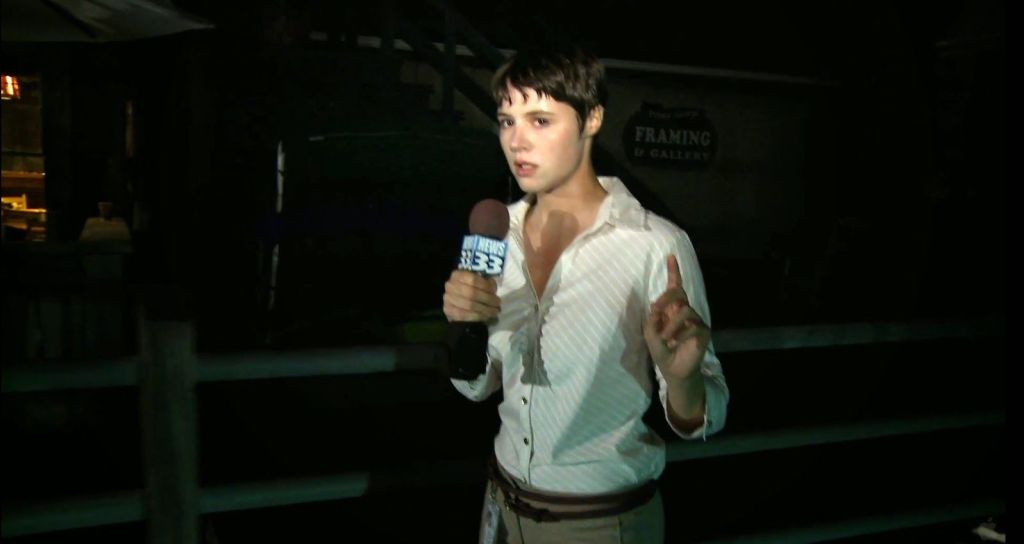

The movie recalls the quietly unsettling events of a community fair by a beachside bay community that has long relied on the local water supply for sustenance and recreation. However, chemicals and excrement from the local poultry plant have contaminated the water and the locals have started voicing their concerns about the water quality, despite the mayor’s insistence that the water is perfectly safe, doubling down on the importance of Claridge’s growing economy. A rookie reporter (who will later leak the story to the press) is meant to report on the parades, the crab-eating contests, and the other fair activities, but slowly begins to understand the enormity of the situation as more and more people begin to succumb to the mutated microbes that threaten to decimate the community.

Directed by Barry Levinson, The Bay represents a significant departure from the filmmaker’s other efforts. Beyond the obvious foray into found footage film, the film lacks any of the humor of some of his other movies. There is no shortage, however, of the social consciousness that permeates Levinson’s other films, whether the anti war sentiments & freedom of speech stance of Good Morning Vietnam (1987) or the mass media criticism that seasoned movies like Quiz Show (1994), Wag the Dog (1997), and Bandits (2001). For now, The Bay is Levinson’s unapologetic prediction of ecological collapse, and the audience is complicit in the consequences: If man is the puppet master who orchestrates ecological erosion, then man must stand witness to it through the unique storytelling of the film itself.

The film’s narrative is creatively culled from multiple media sources — first from a Zoom interview with the whistleblowing cub reporter, then from news footage of the ribbon-cutting ceremony at Claridge’s fair, then from multiple home movies recorded by local citizens. These vignettes — peppered as they are throughout the film — are not meant to inspire the audience’s immediate participatory dread generally associated with found footage films. This is not a traditional genre film in which the audience is meant to experience the horror as it plays out in real time for the film’s victims. On the contrary, the collected footage is shared — like that of The Blair Witch and Cloverfield (2008) — with the audience now as a series of moments that cannot be controlled, are not meant to be controlled. As the ecological threat begins to grow more and more deadly — killing two teens while swimming, a number of citizens reporting the appearance of boils and lesions on the surface of the skin, several feeling the physical discomfort of bugs freely moving about within their host bodies — many of Claridge’s community die within hours of exposure.

As a piece of ecological horror, The Bay is most effective in establishing the isolation that the film’s victim — namely, Claridge itself — must experience. The community of Claridge all but experiences quarantine — especially unsettling nature of a pandemic that makes the hopeless despair in Claridge feel a little too close to home for viewers. Followed on those heels by the CDC’s admission that no help will soon arrive — followed even more on those heels by Homeland Security’s assurance that what Claridge is experiencing is an isolated incident that will resolve itself in time with little collateral damage — and the nightmarish isolation of the ecological horror story is complete.

The hopeless state of survival is further accentuated by the found footage approach of the film. By the film’s construction, these are events that have happened, fully concluded, with no respite from the lifeless bay that people will find once they arrive there, and the audience is held captive by that realization. A nihilism begins to take shape in Claridge that is further demonstrated through the unavoidable circumstances of the tragedy. Oceanographers are able to conclude that a population of harmless baywater louse has mutated due to the growth hormones meant to provoke rapid growth in the chickens (thereby transplanted into the bay through excrement), and what begins as multiple fish eaten from the inside out transforms into a swarm of isopods just as dangerous to the human population that has enjoyed the peaceful Claridge waters for so long.

The film’s thesis becomes one of desperate conclusion. Almost half of the community’s population — water-based and beachside — is killed by an epidemic that was willfully ignored by community leadership that saw more profit in exponential economic growth than saw a danger in the abnormal growth of invasive species. Even Donna — the reporter determined to deliver the news of this tragedy to the world — openly believes that her life is in danger from governmental agencies.

And there is no indication through the exposition of the film’s final moments — against a hauntingly fatalistic backdrop of beachside recreation, despite the loss of life — that anyone is safe anymore.

Not Donna. Not the immediate community of Claridge. Not a world that appears to willfully traffic in life-threatening profit at the expense of the people, in life-changing prosperity at the expense of the land.

Levinson’s film, then, becomes an exercise not only in the evolutionary possibilities of the subgenre of found footage films but also in the prescriptive and immersive nature of ecohorror. As isolating and devoid of hope that the narrative may be, the consequences of The Bay demonstrate a zero sum outcome as pervasive as an epidemic itself, signaling the inevitable destruction of which Levinson warns and of which the world — the world of the film, the world of the moviegoing audience — is doomed to play a role. The ecological tragedy of the film is in and of itself a mutating thing: propagated by the community’s elite that puts the facade of safety over the sanctity of life. And upon viewing the film, viewers allow the transformation to complete itself, unfolding through the multiple lenses utilized by this mutation of an already revolutionary style of horror filmmaking.

***

This piece — written by Justin Howard Query and after some additional editing here — was originally published by another source.

Leave a comment